A Race To Protect The Crumbling Bricks Of Ancient Babylon

By Jane Arraf

November 24, 2018 – Mohaned Ahmed is standing on scaffolding at the ancient site of Babylon, dipping water into a bucket and sponging the bricks around a stone relief showing a dragon with a serpent’s head.

The image is so well defined it looks as if it might have been made yesterday instead of more than 2,000 years ago. But below it, the bricks and mortar of one of the ancient world’s grandest cities are disintegrating.

Ahmed is part of a team of about 10 Iraqi technicians trained by a U.S.-funded project to shore up the brick walls of the ancient site of Babylon, some 50 miles south of Baghdad. The goal is to improve Babylon’s prospects of being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a designation that would help ensure better protection and preservation of the site and encourage future tourism.

“Babylon was the first city in history. We want to work here because we love this city,” says Haider Bassim, 29, an Iraqi technician who grew up within the perimeter of the ancient city.

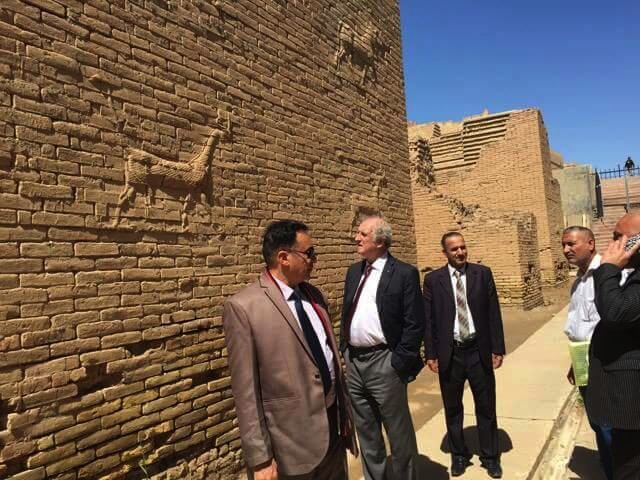

“You have to look at masonry work a bit differently when you’re holding a thousand-year-old brick, and I think they’re getting more sensitivity for the materials and respect for the monuments,” says Jeff Allen, an American conservationist with the World Monuments Fund, a New York City-based heritage preservation group.

Allen, who oversees the Iraqi trainees, has been working at the Babylon site over the past nine years. His current project, funded by the State Department and others, is part of the World Monument Fund’s Future of Babylon program, which aims to preserve the site.

Initially, the goal was to stabilize ancient walls and roofs in danger of collapsing. Now, an important part of the program is training local technicians, most of them farmers and laborers from nearby villages. The hope is that they will come away with useful skills in a region with high unemployment – along with the desire to help protect Babylon.

Centuries-old scars

For decades, the site has come under repeated threat, even from attempts at restoration. In the 1950s and 1990s, for example, damage was done when mid-sized modern bricks were installed and poured concrete trapped saline groundwater underneath the site.

“The salt gets into the brickwork and it dissolves the brickwork matrix and the bricks just fall apart,” explains Allen, crumbling the corner of a brick with his hand.

In the early 20th century, when Iraq was ruled by British mandate, a railway ran through the remains of the ancient city. After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, military helicopters landed right on the site. The Polish military, part of the U.S.-led coalition, operated an army base in Babylon, building guard towers and erecting fences.

The Iraqi oil ministry even ran a pipeline through the site and was only forced to remove it last month, after the antiquities department took the ministry to court.

The damage and neglect are part of the reason Babylon has never qualified as a World Heritage Site. But all of the site’s more recent scars deserve to be considered part of its cultural heritage, Allen argues.

“These things that were done to the site, they’re irreversible. So stop thinking that’s your obstacle to understanding the site and say that’s part of its history,” he says.

Allen says he would have kept the Polish military watchtower, which was demolished a few years ago, as a reminder of Babylon’s more recent military history.

“I would have thought that was an ideal location to create a memory of an event that was here,” he says.

“So that mankind may gaze on them in wonder”

At its height, Babylon was the largest city in the world — the capital of the Babylonian empire, with an estimated 200,000 inhabitants. King Nebuchadnezzar II is credited with having created the terraced Hanging Gardens of Babylon some 2,500 years ago, said to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

The Biblical legend of the Tower of Babel was believed to be based on a real Babylonian temple tower soaring 300 feet — so high it could be seen in neighboring cities.

The site of the ancient city spans almost 4 miles by 2 miles. Built on layers, only a small part of it has been excavated. The top layer of the city’s massive Ishtar Gate was excavated by German archaeologists starting in 1899 and reconstructed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

A cuneiform inscription from Nebuchadnezzar’s era, removed to the Pergamon, describes the wonders of the city:

“I had them made of bricks with blue stone on which wonderful bulls and dragons were depicted,” the inscription reads. “I covered their roofs by laying majestic cedars over them. I fixed doors of cedar wood adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that mankind may gaze on them in wonder.”

What remains today is an impressive and eerie array of some of the original brick walls lining wide streets that led into the city. On weekends, the site is often filled with Iraqi visitors. Otherwise, it’s deserted. Wind and sand whip through a courtyard with buildings housing a museum and souvenir shop, closed for years now due to lack of visitors. A metal post office box, where visitors could mail postcards in the 1990s, stands rusted and abandoned.

Babylon was one of the most reviled cities in the Bible, condemned to destruction for its wickedness. Its Biblical reputation could well have been due to its size, says Olof Pedersén, a professor of Assyriology at Sweden’s Uppsala University working on the Future of Babylon project.

“It was the largest city, and the largest city of course always gets a bad reputation from people who don’t live in large cities,” says Pedersén. “You can do a lot of things in large cities which you cannot do in a little village.”

In the Quran, the city is cited as a source of black magic. Today, off the beaten track from the excavated city, fenced off by wire, are the remains of a well where legend has it that two wayward angels — mentioned in the Quran as coming to Babylon to practice magic — were hung upside down.

Pride in the past, but not in its artifacts

Despite Iraqi pride at laying claim to a heritage that produced the world’s first code of law and first cities, Iraqis don’t necessarily value their country’s archaeological sites. “You came from Baghdad to see these ruins and dust?” a surprised policeman asks visitors at a security checkpoint near the site.

For centuries, people in the area saw Babylon as a source of solid bricks to take away to build homes in the city of Hilla and surrounding villages. Over time, townspeople removed an entire top layer of the Ishtar Gate and threw away the ornamental glazed blue bricks that were later reclaimed to make up part of the reconstructed gate in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

Allen says it’s just as important to create a culture of heritage conservation as it is to shore up the physical walls of Babylon.

“In Europe or North America, we’re used to studying conservation,” he says. “These kind of programs don’t exist in this region and yet they have this incredible inventory of historic buildings.”

As a first step, Iraqi engineer Salman Ahmed is mapping the excavation — using an app to document each of the roughly 30,000 bricks, down to the cracks and graffiti.

If Iraq’s application for Babylon to be named a World Heritage Site is accepted, it would give Iraq’s antiquities department more power within the government to protect the site. It would also provide an incentive for more tourists to visit, and possibly, more archaeology.

Only 10 percent of the surface layer of Babylon has been excavated, says Pedersén, who first visited as a student in 1979. He still gets excited about it.

“Almost everything is unexcavated,” he says, walking through the ancient streets. “We know the names of the different temples and approximately where they would be. But no one has ever touched them. There is an enormous amount of new things that can be discovered here and hopefully will be discovered in the coming decades.”